Everyone Wants to Lower Drug Prices, But No One Can Settle on a Plan

Both Trump and Democrats say they want lower prescription drug costs.

But they are going about it in remarkably different ways. Indeed, Democrats are split over the usual questions of whether to accept half a loaf in order to show some progress.

For his part, Trump’s talk is bigger than his results—much bigger. A report by Senate Democrats finds that the prices of the 20 most-prescribed drugs under Medicare have increased substantially over the past five years, rising 10 times faster than inflation.

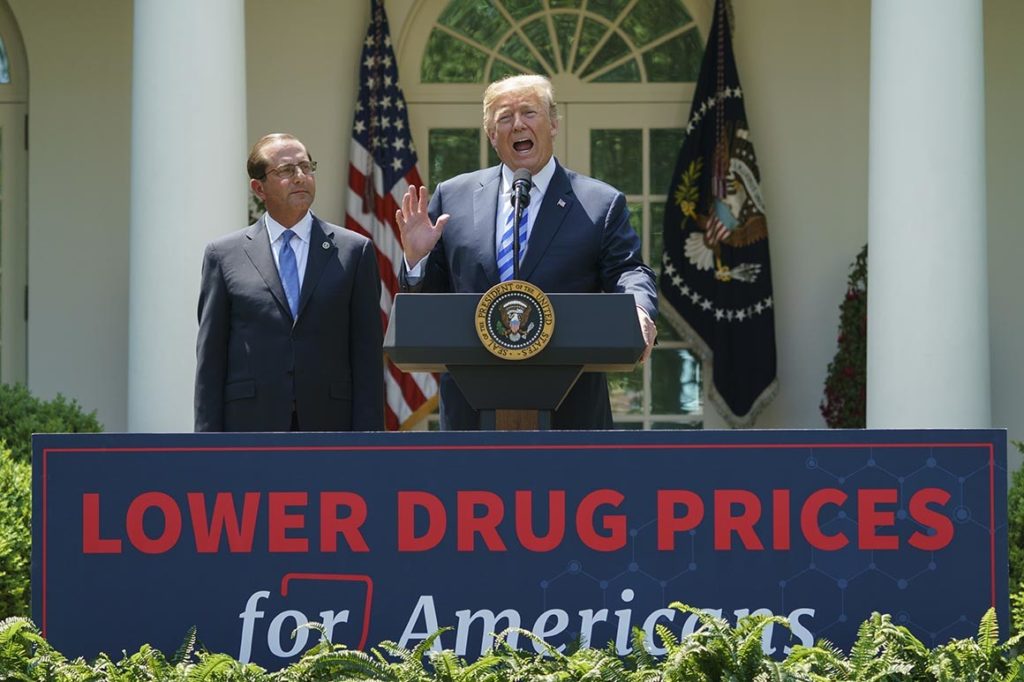

Trump’s preferred approach is to go after fraud and marginal issues like the costs related to doctors who over-prescribe medicines targeted at them by pharmaceutical companies. Trump has installed Alex Azar, a former Eli Lily executive, as his secretary of Health and Human Services and Scott Gottlieb at FDA—both of whom support deregulation of the industry to promote competition—as well as other lobbyists for Big Pharma in subordinate positions.

But Trump stays away from unleashing the negotiating power of Medicare/Medicaid to leverage membership against prices. Basically, he trusts the power of the marketplace.

Among Democrats, there seem to be three general approaches.

The presidential candidates, including Bernie Sanders, but also others, favor a “Medicare for all” approach to health care to set the prices of prescription drugs in line with international price structures—at substantially less than current U.S. market prices.

The U.S. pays the highest prices in the world because the government grants long-term monopolies to pharmaceutical firms and then refuses to regulate the prices companies charge.

Congressional Progressive Caucus members have introduced several bills that aim to take pieces of the problem, like setting U.S. prices consistent with international drug prices (Sanders and Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., and Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore.). Another mandates that Medicare be freed to negotiate with Big Pharma (Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Texas).

And Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) seems to be favoring a negotiation with the president to produce a system of arbitration run by an independent agent.

So, in reaction to continuing high prices, we’re seeing some splits in how we should go about solving the problem. “Any bill that allows Pharma to engage in arbitration is inconsistent with a real effort to hold Big Pharma accountable,” said Khanna, who is vice chairman of the Progressive Caucus. He was careful to note that he was not speaking on behalf of the group’s leadership. “The Democrats should at the very least get behind” price negotiation with the threat of ending drug monopolies.

Doggett chairs the Health Subcommittee on the Ways and Means Committee, so his bill would be the logical starting point for a drug bill under ordinary congressional procedure. But big-ticket legislation has been bypassing the committee process since the Obama years. Most major bills in recent years have been negotiated between the White House and congressional leadership.

Meanwhile, the United States pays the highest prices in the world for the most popular prescription drugs, because the U.S. government grants long-term monopolies to pharmaceutical firms and then refuses to regulate the prices companies charge. Drug prices are thus immunized from both market competition and government pressure.

Pharmaceutical lobbyists and executives insist that these monopoly profits are necessary to foster innovation, but there isn’t much evidence to back up their claims. Pharma companies do make a lot of money, but they don’t spend much on actual scientific research.

The Huffington Post reported recently that since at least 2006, U.S. pharmaceutical companies listed in the S&P 500 have spent more money on stock buybacks and dividends than they have on research and development. The prescription drug business is consistently the most profitable industry in the world, but according to a recent study by the economists Öner Tulum and William Lazonick, these profits are simply turned over to shareholders rather than reinvested in public health. And shareholders, in general, are rich people―80% of all stock wealth is controlled by the wealthiest 10% of the population. And some of the richest shareholders in America are pharma execs, who receive about 80% of their compensation in company stock.

The Huffington Post argued that one could reasonably conclude that the chief product of the American pharmaceutical complex is not medicine, but inequality. Other countries pay less, innovate more and live longer.

It was a big deal when Pelosi made lower prescription drug prices a central policy issue of the 2018 midterms. The language she’s used against Trump in public has been unsparing; in October she tweeted that Trump was “letting Big Pharma walk all over him.”

But in private talks with the Trump administration, Pelosi’s office has been pursuing a much softer line. According to Politico and the health and medicine news site Stat, Pelosi’s team wants to identify overpriced drugs and sort out lower costs for consumers through arbitration, rather than regulation or the federal court system. Large corporations typically prefer arbitration as a method for resolving disputes with customers, because the private arbitration process is more favorable to corporate interests than public courts.

Under the arrangement currently being pursued by House leadership, the government would forgo direct price negotiation or regulation and instead cede pricing authority to an independent arbitration firm. It’s not clear what the precise rules of the process would be.

Pelosi will likely face increasing opposition not only from some of her progressive members but also from left-leaning groups advocating a tougher approach.

The problem with arbitration, however, is that Trump already has more powerful tools at his disposal to lower drug prices―and he doesn’t need to ask Democrats’ permission to use them.

The federal government has the power to issue what are called “compulsory licenses”―a special contract that allows a competing company to sell a product that another firm has patented. It’s a clunky process, and most drug price reform advocates want legislation to get prices down. But in a pinch, Trump can just identify overpriced drugs and allow a competitor to start selling them at a lower price. He doesn’t need Pelosi’s help or Pharma’s permission.

If Trump were serious about lowering drug prices, he’d be asking for Democrats’ help to strengthen his ability to use that tool. That’s how Doggett’s bill works. An arbitration bill, by contrast, would provide a Democratic Party endorsement for Trump to tout a symbolic half-measure.

No president has ever actually used compulsory licensing authority for prescription drugs, but the practice is common in other countries. In 2012, the government of India issued a compulsory license to bring down the price of a cancer drug from over $5,000 a month to $157.00.

But after two years in office, Trump has not played hardball with Big Pharma—despite his campaign promises and calls while in office to lower drug prices. On trade policy, the Trump administration has actually strengthened the pharmaceutical industry’s ability to charge monopoly prices by bolstering intellectual property protections for biologics― drugs made of living organisms, which have recently been a source of expensive new cancer treatments. Meanwhile, the administration wants to let states sell junky short-term health plans that skirt Affordable Care Act requirements and do not cover prescription drugs.

“So far, this Administration has talked a big game on tacking drug prices, but they haven’t delivered,” Khanna concluded. “If [the administration was] serious they would back Sanders and my legislation or the Doggett bill.”

Featured image: Trump and Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. (AP)