It’s Labor Day, and Worth Noting that His Trade War Isn’t Bringing Back Jobs From China

If you believe even a scintilla of the Chinese trade talk from the White House, you likely accept the notion that these trade disputes are bringing companies and jobs back to the United States.

Here’s my question: Is it true?

If the companies and jobs are not coming back, where exactly is the beef of this conflict?

As it turns out, there is no central accounting for such job transfers, but what seems to be happening is that companies made unhappy with the trade situation are moving to other countries with low wages – including Bangladesh and Vietnam – or simply increasing the output of goods produced in China for an Asian market rather than for the United States.

Companies who might consider returning jobs to the U.S. face the prospects of investing in plants that will pay much higher wages, tariffs on imported parts and supplies.

Meanwhile, of course, U.S. companies that have been adversely affected are in search of supply lines and markets outside China. Those companies who might consider returning jobs to the United States face the prospects of investing in plants that will pay much higher wages, tariffs on imported parts and supplies as well as other uncertainties of the U.S. economy.

My conclusion: The effect of trade wars will not be immediate, and is unlikely to produce the results that Donald Trump promises.

Jobs for Cambodia

Politico and the South China Post recently looked at a bicycle manufacturer with plants in Shanghai and, since 2014, in South Carolina. Indeed, there was a big to-do in South Carolina when Kent International announced grand plans for expansion. Today, production at the Shanghai plant is moving to a planned new factory in Cambodia, and the South Carolina effort has met tariffs on steel parts that have stalled any plans to bring jobs to the United States. Rather than buy those component parts in America, this company finds imports cheaper; rather than move the manufacture to South Carolina, those Chinese jobs are now going to be Cambodian jobs.

It would appear that companies leaving China are headed for cheaper labor markets in Southeast Asia.

Overall in the United States, manufacturing job trends are seen as cooling and national economic growth has slowed. The latest U.S. jobs report showed manufacturing employment rose by an average of 8,000 per month in 2019, compared with an increase of 22,000 jobs per month in 2018. Job additions have been revised to be a half-billion less than first reported nationally, and the rate of growth has been refigured to about 2.5% a year.

The Coalition for a Prosperous America, a backer of Trump’s tariffs, has estimated that the Chinese tariffs could create more than a million U.S. jobs in five years; instead, those jobs so far seem to be going elsewhere in Asia. That group now favors cutting off Chinese trade altogether, a position that Trump has adopted, disowned, and then sort of backed again. Trump has gone so far as to describe emergency powers by which he could force U.S. companies to quit China before saying he does not intend to use the laws now.

“Tariffs are a great negotiating tool, a great revenue producer and, most importantly, a powerful way to get companies to come to the USA and to get companies that have left us for other lands to COME BACK HOME,” Trump tweeted last month.

For sure, there have been some announcements from companies about bringing jobs back to the United States. Stanley Black & Decker said this year it would move production of its Craftsman line of tools, which it acquired from Sears, from China to Texas, adding 500 jobs. Restoration Hardware is another, saying in a recent earnings report that tariffs were spurring it to bring some manufacture to the U.S.

The U.S. Commerce Department published this year a “case study” on reinvesting in the U.S., highlighting the experiences of six companies moving production to America. The report makes the case “that anecdotal evidence of hundreds of reshoring cases is very real,” but it also admits that tariffs are a “challenge” for companies wanting to move production to the U.S.

Half of the companies profiled by the Commerce Department highlight the harm of tariffs on investment decisions, but also cited difficulty finding trained workers, uncertainty about regulations and a more expensive-than-planned transition.

‘Modest Effect’

Harry Moser, president of the nonprofit Reshoring Initiative, told the South China Post that he agrees 100% with the goals of Trump’s tariffs, but said they have had a “modest net negative” effect on jobs coming back to the U.S. as companies look elsewhere to relocate production. Reshoring did a study that showed 2018 moves already were waning by this year.

The South China Post talked with a Hong Kong-based supply chain inspection company which said neither China nor the U.S. is winning the trade war. The company, which has 6,000 clients worldwide, has seen a 13% drop for China-based inspections from U.S. companies, while seeing increases of work for U.S. companies increase 21% in Vietnam, 25% in Indonesia and 15% in Cambodia. Mexico inspections for U.S. clients jumped by a staggering 119% in the first six months of 2019.

For other companies, the threat of intellectual property theft and not tariffs has driven decisions to relocate production to the U.S. An Ohio toy company reported that one brand returned work from China to an existing plant in Hudson, Ohio, in a bid to avoid fake versions of its products from being sold to consumers, noting that the counterfeit manufacture also was producing unsafe goods.

Still, the firm said that were it not for having an existing plant, the company would have considered moving production elsewhere in Asia to avoid labor costs.

It sounds to me that we should be wary of claims of the U.S. gains from tariffs on China.

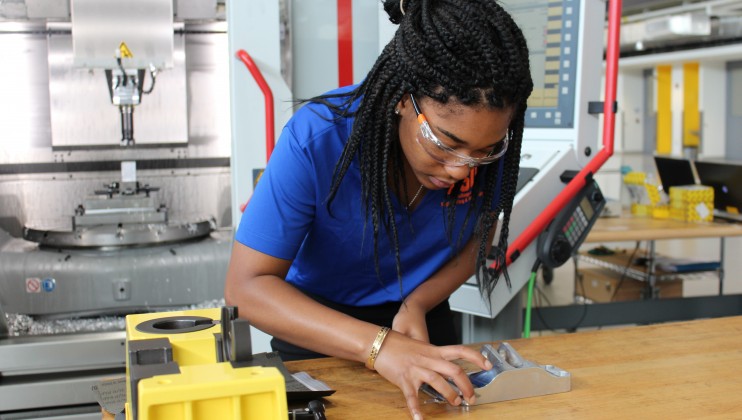

Featured image: Commonwealth Center for Advanced Manufacturing (Virginia)