Community Theaters, Opera Companies Hit Hard in the Pandemic Still Struggle; Two-Thirds of Grant Requests Not Paid

Few organizations suffered more than nonprofit performing arts venues in the past 16 months of the pandemic. Continued uncertainty surrounds reopenings, in part because of the achingly slow government response in delivering money needed to resume performances.

Unlike restaurants and bars, which have minimal costs to resume operations if they held onto their space and inventory, many performing arts venues say they can’t just open up because they need money to rehearse, build sets, advertise, and produce events.

Live performance charities big and small are in deep financial holes. The Metropolitan Opera in New York faces a colossal shortfall of $150 million, Operawire reported. The Opera projected to bring in $49 million in box office revenue this fall, $88 million less than its earnings from the 2019-2020 season that was halted by COVID-19.

Live entertainment venues were among the first businesses to close, and they will almost certainly be among the last to reopen. Sen. Amy Klobuchar

This estimation last year came alongside Metropolitan Opera General Manager Peter Gelb’s prediction that it would take years for the company to rake in its usual totals again due to the bleak outlook for tourism, according to Operawire.

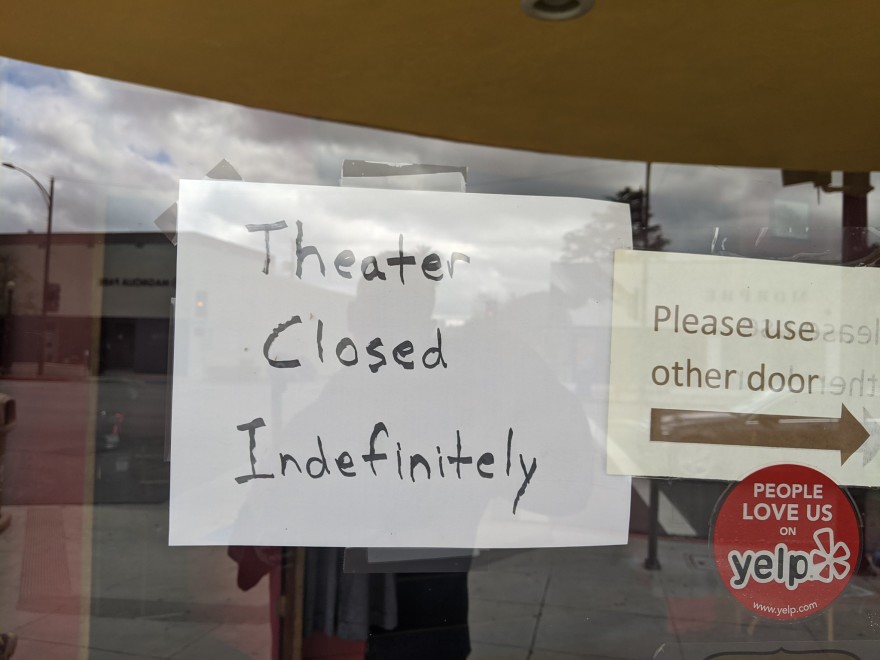

The Bootleg Theater, a staple of Los Angeles’ arts and cultural scene for over two decades, was not as lucky. It was forced to close its doors just as the city began to reopen.

“We are in a public health and economic crisis, and the live entertainment industry has been particularly hard-hit during the coronavirus pandemic,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) said on the Senate floor in December. “These live entertainment venues were among the first businesses to close, and they will almost certainly be among the last to reopen.”

Half Closed

Almost half of the nonprofit arts and cultural organizations with in-person programming remain closed, and roughly half of those have no scheduled return date, Americans for the Arts found in a June 28 survey.

Many of those nonprofits said they lack funds to reopen. More than two-thirds of these lightly financed arts organizations said they expect that raising enough money to open the doors again will take three months or more, according to the survey.

In an updated report two weeks later, Americans for the Arts reported 39% of organizations with in-person programming still remained closed to the public. Most of these groups aim to resume in-person activities this year.

Many nonprofit theaters have no working capital. Like millions of cash-strapped Americans, they struggle from performance to performance, not unlike those who live paycheck to paycheck with no savings.

ACTION BOX / What You Can Do About It

Artists, performers and writers can find useful resources to help them through this phase of the pandemic at Poets & Writers and Backstage.

Performing arts nonprofits and venue operators can use this directory hosted by Americans for the Arts or this list composed by the National Endowment for the Arts to stay up to date on legislation and news related to the arts within their state and nationwide.

Tell your representative or senators about the SBA’s sluggish response to helping struggling performing arts organizations.

“When you produce a show, you’re banking money to produce the next show,” said Chris Serface, President of the American Association of Community Theaters.

Serface is also managing artistic director for Tacoma (Wash.) Little Theatre. “We’ve been dark for a long time, so we don’t have that capital to just go ahead and produce a show again,” Serface told me.

As if financial instability was not enough to endure, even though Congress appropriated money for live performance venues, so far only a trickle of cash flows to them, Serface and others said.

The Save Our Stages Act — a bipartisan bill spearheaded by Klobuchar and Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) — was included in the $900 billion stimulus bill last December. It allocated $15 billion for struggling arts and cultural locales through the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant program.

Slowdown at the SBA

The arts and similar grants, administered by the Small Business Administration, were supposed to be easier to apply for than the Paycheck Protection Program loans.

The rollout was shaky at best. Weeks after the early April start date, the SBA blamed “technical difficulties” for not approving requests and sending funds. SBA reported on June 9 it had issued grants to less than 1% of more than 14,000 applicants.

Christopher Mannelli, executive director of the Geva Theatre Center in Rochester, N.Y., applied for a grant in April. It took two months for SBA to notify him that the agency had reviewed his paperwork.

“It’s supposed to be emergency funding, and it certainly has not arrived in a timely manner at all — and all of us have emergency needs,” Mannelli said.

The SBA’s latest report detailed a significant improvement in the distribution of grants because the program got off to such an atrocious start.

The agency has distributed almost 4,000 grants since the earlier debacle at the beginning of June, according to its July 6 report. That’s less than a third of the grants sought.

And aside from the bipartisan criticism voiced by Cornyn and Klobuchar of SBA for its botched implementation, there is no indication of more federal help soon.

“I fully expect the performing arts field to feel this is a two-to-three-year pandemic,” said Tamara Keshecki, a research associate at UMass Amherst School of Public Policy. She is also on the New York Independent Venue Association board, which represents independent performing arts groups and organizations based in the state.

“It’s not going to be like ‘we got some grant money, we reopen, and everything goes back to business as normal,’” Keshecki said.

In June, Washington state lifted most COVID-19 restrictions, joining virtually all other state governments in allowing enterprises to function at full capacity. But Serface said that doesn’t guarantee audiences will resume buying tickets.

His theater welcomed some people to its summer youth program at the beginning of July, but Serface said there’s no way to predict how willing audiences will be to return.

Still, the Tacoma theater plans somehow to resume shows in the fall, when the production season usually begins.

“That’s the big question none of us really know the answer to because it’s different all across the country,” Serface said. “There’s a lot of variables that are making a lot of people nervous, and those are some of the struggles we’re all going to face going forward.”