The Fallout After California Cops Crack a Cold Case Using a Genealogy Website

Just as we collectively are beating up Facebook—globally, mind you—for sharing or selling our personal data without express permission, now comes the news that authorities found an old serial killer suspect by using shared digital personal data.

Use of DNA results used in solving a California serial killer case and obtained from a genealogy research company is testing privacy concerns in the digital age.

A popular First World temptation is to find out more about from whence we came. So there are multiple genealogical companies competing to deliver supposedly scientific information, for a price, along with whatever records there are about when grandpa arrived on Ellis Island.

We open ourselves to examination of our most personal medical information only to find out that the information is being shared with law enforcement—without our permission or even knowledge. On a widespread basis, I suppose this means the government, which has a penchant for doing such things, can build a national database of DNA samples to consult after any crime, without notice and apparently without seeking prior court approval.

Hypocrisy of the Week

The National Rifle Association has banned guns when Vice President Pence speaks at its annual meeting in Dallas on Friday, sparking criticism from Parkland, Fla., students, who say schools should be afforded the same protection as some of its members.

Isn’t this the exact thing that the Congress just called Mark Zuckerberg to testify about … that his Facebook listings are not offered with the idea that they will be shared with outside third parties?

Hey, in a medical office, my wife cannot get my results from any medical test, even if it somehow were just a matter of convenience. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules govern and privacy is a matter of insistence. But finding DNA results through these more popular sites is more akin to Facebook.

A Newsweek story attested to the growing popularity of DNA testing, but questioned the validity of some of the results. Last January, The New York Times wrote of efforts to trace male lineage through some specific cases, finding that newer tests can survey the DNA from either parent, but at a cost of precision about areas of origin.

In the recent California murder case, law enforcement authorities apparently did not even inform GEDmatch, a genealogy site, that they were using its free database to track down a suspect in a string of decades-old serial killings and rape, according to Curtis Rogers, a co-founder. “This was done without our knowledge and it’s been overwhelming,” Rogers told The Associated Press. Rogers insisted the company does not “hand out data” and told the AP that the incident raises privacy concerns.

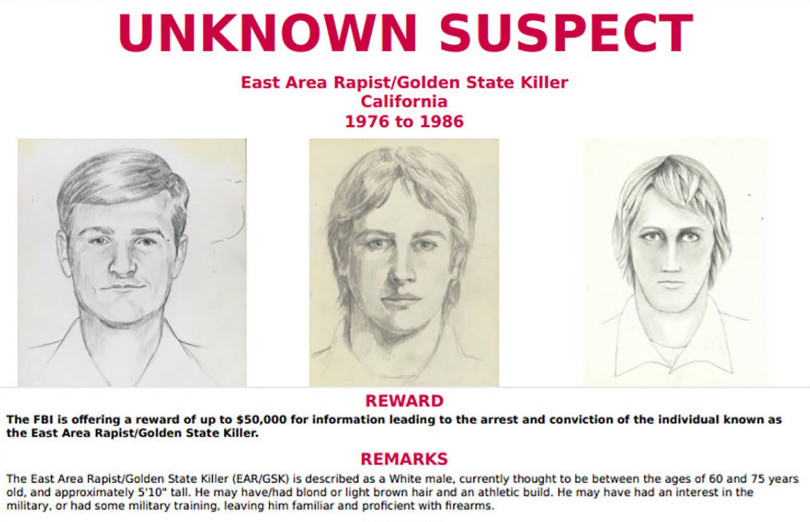

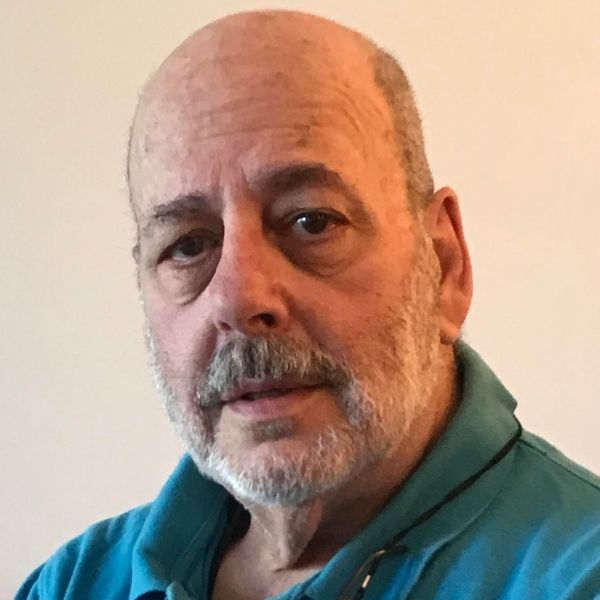

As a result of seeking a match with crime scene DNA with a sample on GEDmatch, authorities charged Joseph James DeAngelo, 72, who they suspect of being the East Area Rapist, a serial killer who terrorized California in the 1970s and 1980s, with eight counts of murder.

GEDMatch is a free site where users who have obtained DNA profiles from commercial companies such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe can upload them to expand their search for relatives. Ancestry.com and 23andMe have said that they were not involved in the case. Major for-profit companies do not allow law enforcement to access their genetic data unless they get a court order.

Ancestry.com has a privacy policy which is pretty clear. But the question here is about the site that aggregates the results from several companies and has none.

Paul Holes, the lead investigator on the case, told The Mercury News in San Jose, California, that the investigative team used GEDMatch to find a relative, a move that eventually led to the arrest. As The Mercury noted, “The case sheds light on a little-known fact: Even if we’ve never spit into a test tube, some of our genetic information may be public—and accessible to law enforcement. That’s because whenever one of our relatives—even distant, distant kin—submits their DNA to a public site hoping to find far-flung relations, some of our data is shared as well.”

The paper quoted law school professors who suggested that even companies that promise privacy may be required to surrender your genetic data if confronted with a search warrant. “As more and more genetic information becomes available, its possible use in criminal investigations becomes more and more feasible, both for direct checking and familial checking,” said Stanford University School of Law professor and bioethicist Hank Greely, director of Stanford’s Center for Law and the Biosciences. “That’s true whether it’s a genealogy database, electronic health record or research.”

So, in pursuit of preening ourselves with electronic tools, in fact, we are opening ourselves open to more and more apparently legitimate snooping into those details.

We ought to acknowledge that and put some regulations in place that insist that we are notified in plain language that this is a possibility.