This Effort To Resist Learning Is Seen as a Political Plus

There’s a reason that democratic nations resist negotiating with terrorists even for the return of hostages: Paying the demanded ransom only promises more of the same.

That’s the context of this week’s apparent cave-in by the College Board to winnow its Advanced Placement Curriculum for African American Studies after focused criticism by Republican Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and his budding presidential platform based on a broad attack on all policies, programs, and attitudes that he sees as reflecting a “woke” outlook in education and business.

Protestations from the College Board notwithstanding, the announcement that the education professionals would remove Black authors who promote apparently controversial, critical thinking subjects came across as a blatantly political surrender to right-wing complaints about perceived “indoctrination” of our best high school students — students who are adjudged as able to meet challenging interdisciplinary courses laden with hefty questions that question the status quo.

Indeed, a course on the African American experience redesigned by a conservative political camel in pursuit of whitewashing controversy raises questions about why there is an Advanced Placement course at all.

In any event, the College Board surrender came just as DeSantis – who is seen as “building his brand” by remaking higher education to denude it of multiculturalism – was already busy pushing beyond the AP course skirmish to demand state public college curricula that stress Western Civilization history, the elimination of any programs mentioning diversity and inclusion, and generally attacking the idea of academic tenure. He is out to eliminate what he calls “ideological conformity,” even as he increasingly cites conservative resumes as a qualifying element for appointment to state college education jobs. He sees “indoctrination” in examining questions, that this course and others even remotely related are not historically accurate and they violate a state law he created to insist that no course could be taught that might make a student feel shame.

Further, DeSantis sees himself a leader among two-dozen states whose Republican-majority legislatures share the goal of protecting a dwindling national White, Christian-identifying population intent on resisting the natural course of demographic change. Somehow, in a world that I clearly do no inhabit, this effort to resist learning is seen as a political plus.

Curtailing the Course

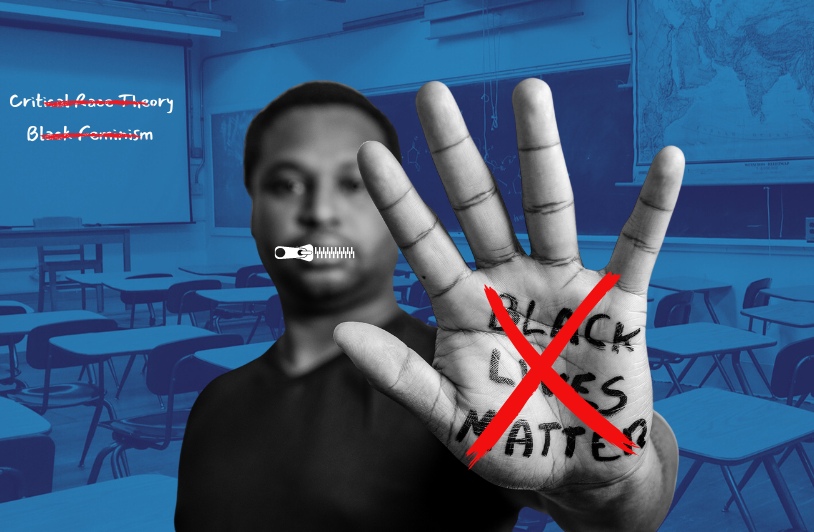

In its announcement, the College Board eliminated from its nationally recommended AP class many Black writers and scholars associated with critical race theory, the queer experience, Black feminism, and mentions of Black Lives Matter. It added an idea to research “Black conservatism.”

Stretching credulity, David Coleman, head of the College Board, told The New York Times that the changes were all made for pedagogical reasons, not to bow to political pressure. “At the College Board, we can’t look to statements of political leaders,” he said. The changes, he said, came from “the input of professors” and “longstanding AP principles.”

Maybe we should have an Advanced Placement course about the selling of bridges in Brooklyn and the discerning of meaning and language. Naturally, it would have nothing at all to do with American politics.

Let’s just acknowledge that we find ourselves in a huge insurrection about what it means to be an American, about how we look at race and identity in all phases of our society. The messy part of rights and democracy revolves around the central question of how to extend these rights to parts of society who have been pushed aside.

It is simply astounding to have an announcement about cutting out critical questions about race in education in the same week in which we are witnessing the public anguish over how to think about community policing that results in the death of another Black man stopped over an alleged traffic stop in Memphis and the firing and arrest of at least five police officer for the killing.

It is one thing for the DeSantis crowd to question age-appropriate mentions of race and identity in schools and quite another to ban diversity programs for colleges and private businesses. It is unwise to tell students who volunteer to undertake a challenging college-level high school course that crosses academic disciplines that they are wrong to have questions about the teachings of American history, sociology, and other social sciences.

Why the College Board would give in here likely has a lot more to do with the business aspects of the education panel and acceptance by conservative state officials than its views of academic rigor. AP courses are a major source of revenue, said The Times, which checked its nonprofit income forms. Two dozen states have adopted some sort of measure against mentions of critical race theory, which is not taught in public schools outside of this AP class meant for advanced placement in college.

Cutting Contemporary Issues

Obviously, the dispute over the advanced placement course is about attitudes towards race and gender issues altogether, themes reflected in our steady march of state legislations and court cases aimed at trimming affirmative action, housing, immigration, education, and other areas of dispute.

If we all were to accept the findings of this course, we would not have need of it. But race has been this nation’s Achilles’ heel through three centuries.

The revised 234-page curriculum includes content on Africa, slavery, reconstruction, and the civil rights movement. It is the discussion of more contemporary topics from affirmative action, queer life, the possibility of reparations programs, that have prompted protest. Those subjects have been eliminated from course exams or options for a required research paper.

Now banned writers and scholars include Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, a law professor at Columbia, who addresses critical race theory; Roderick Ferguson, a Yale professor who has written about queer social movements, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, who has argued for reparations.

Colleges and universities in America always have taught about Western Civilization. Over decades, it has been the attempt to bring similar academic interest to non-Western societies, indigenous peoples and to those suffering in a striation of American society that has been a continuing focus. Look no further than the news of the week, where confrontations over race in America and our long-term rivalry with China and Asians nations fill the airwaves.

Do you think understanding what America is up against might be more appropriate than not?